Outrageous Predictions

Executive Summary: Outrageous Predictions 2026

Saxo Group

Head of Fixed Income Strategy

There is no doubting that 2017 was an exceptional year for many regions. In this article, however, I would like to focus on an area that lagged its neighbours for many years. I am talking about Central Eastern Europe.

The region's largest economy, Poland, expanded 4.6% in 2017 while the Czech Republic grew by 5.1%; Romania outstripped both with a 6.9% growth rate. The Polish zloty and the Czech koruna, meanwhile, were among the best-performing currencies in the emerging market space in 2017.

Turning to the fixed income market, many countries across this region saw sovereign bond yields fall in 2017 along with corporate yields.

The reasons for this outperformance are tightly linked to the Eurozone as the European Union supports export demand in this area and EU development funds continue to flow into the regional economy. Although there remain signs of weakness, particularly those surrounding the political uncertainty of the region, investors are still putting their money to work in corporate and sovereign bonds, confident that the only direction is up.

After all, if 2017 was an exceptional year, 2018 will be the dream come true... right? Will CEE bond prices remain supported throughout this year?

In order to answer this question, we need to take a step back and look at CEE relative to its neighboring countries.

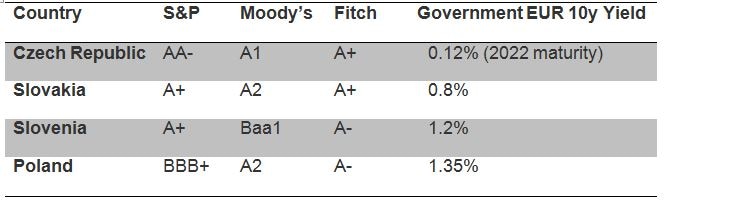

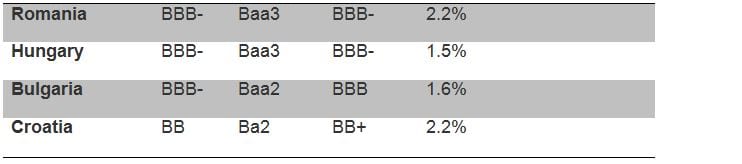

Source: Bloomberg

As we can see, ratings in the CEE region are polarised. The majority of the countries are rated investment grade with Croatia lagging behind as the "black sheep" of the group (its bonds are considered junk and rated BB/BB+ by S&P and Fitch).

Looking at core Europe we see that the ratings for CEE sovereigns are incredibly high. Spain is rated BBB+/A- (S&P/Fitch) at level with Poland, while Italy is rated BBB (S&P/Fitch) and thus stands between Romania and Poland. While Italian and Spanish 10-year government bonds pay respective yields of 2% and 1.5%, 10-year euro-denominated bonds for Poland and Romania offer 1.35% and 2.2%.

CEE should no longer be considered as belonging to the emerging markets basket – these countries, after all, are now part of the EU. We can all agree, however, that the region still maintains EM-style risks such as dependence on stronger economies and political uncertainty.

This should raise red flags for investors. Historically speaking, when countries have defaulted on their debts, they have done so consciously, meaning that the country might have had the funds to repay investors but decided to default anyway. I am not implying that we should expect defaults on sovereign debt in this region, but rather suggesting that institutional risk is often underrated and should not be ignored.

Even if the CEE economy is growing, we see troubling signals such as the rise of populist political parties, a phenomenon created by a popular perception that ordinary people are not benefiting from the expansion. This decreases confidence in traditional institutions such as the EU, increasing volatility in local markets.

The situation is no better in CEE corporate bonds where a lot of domestic and international investors have recently entered this space, eroding any premium there may have been in local corporate bonds. This raises the risk involved with local bonds as they are notably less liquid than other CEE corporate bonds issued in hard currency.

Liquidity is the most important factor for investors to consider now that we have entered a period of high volatility. Liquidity is the key factor that will actually attract more premium as investors realise that when things go down, the only thing that is going to be possible to trade are liquid issues.

This should bring great concern to bond investors holding local corporate and government debt in CEE because as we have discussed above, it is hard at the moment to see liquidity premium in these securities.

As noted, Italian 10-year BTPs pay a yield of 2% while similarly rated, euro-denominated government bonds in the CEE region pay around 1.5% (with the exception of Romania where the 10-year pays 2.2%).

While the euro-denominated Romanian 10-year sovereigns pays 20 basis points more than its Italian counterpart, however, we have to take into account that Italy has a total outstanding debt of approximately $2.4 trillion; Romania has just $76bn in debt outstanding.

Just to give you an idea of the depth of the financial markets in CEE, Poland is the country with the biggest amount of debt outstanding with $285bn, or about eight times smaller than the Italian market.

I personally believe that the CEE growth story is compelling, but credit spreads in this region are too tight and do not take into account the premium necessary to compensate investors for several risks, among which liquidity and institutional risks are the most important.

In a bearish market where interest rates are going to rise, we can expect higher volatility as investors may start to sell off credits perceived as riskier in terms of fundamental and liquidity risk. This may affect government and corporate bonds in the CEE region, regardless of the fact that the economies of these countries are thriving.