Outrageous Predictions

Switzerland's Green Revolution: CHF 30 Billion Initiative by 2050

Katrin Wagner

Head of Investment Content Switzerland

Investment and Options Strategist

This article is part of a four-part mini-series on option assignment—created for investors and active traders alike. Whether you're just starting out or deep into advanced strategies, understanding assignment will help you manage risk and opportunity more confidently.

This is part 2: How to avoid assignment.

Assignment is part of the game when you sell options—but it doesn’t have to catch you off guard. Whether you're an investor writing the occasional covered call or a trader actively managing multi-leg spreads, the key to avoiding unwanted assignment lies in understanding when and why it typically occurs—and taking action before it does.

Let’s start with the core concept: assignment happens when the buyer of an option chooses to exercise it. If you’ve sold that option, you’re now on the hook: you may need to buy or deliver 100 shares per contract. But contrary to what many fear, assignment doesn’t come out of nowhere. In almost every case, the warning signs are right there—if you know what to look for.

One of the most useful indicators for predicting assignment risk is extrinsic value, also known as time value. This is the part of the option's price that reflects time left until expiration and expectations for volatility. The rest of the price is intrinsic value, which is the amount the option is in the money.

As long as a short option still has a decent amount of extrinsic value—say €0.20 or more—it’s unlikely to be exercised early. Why? Because the option buyer would lose that time value by exercising.

But once extrinsic value drops below €0.10, particularly when an option is in the money, the odds of assignment go up dramatically. At that point, there’s little benefit to holding the option, and exercising it to capture intrinsic value becomes more attractive—especially for call buyers just ahead of a dividend.

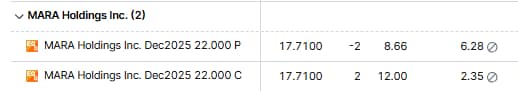

You can estimate extrinsic value in your Saxo platform by looking at how much of the option’s price reflects its time value. Here’s how it works: for a put option, if the strike price is higher than the stock price, the option has intrinsic value. For example, if you’ve sold a put with a €22 strike and the stock is trading at €17.80, the option has €4.20 of intrinsic value—because €22 minus €17.80 equals €4.20. If the option’s current price is €6.30, then the remaining €2.10 (6.30 minus 4.20) represents extrinsic value.

That part reflects how much time is left until expiration and any volatility premium. If that extrinsic value drops below €0.10, assignment becomes more likely.

If the result of the subtraction is negative, that simply means there’s no intrinsic value at all—the option is out of the money and carries only time value. In that case, there is no assignment risk, since exercising an out-of-the-money option would make no economic sense.

Example position with 1 leg (puts) in the money

It’s important to understand that an option being in the money doesn’t automatically mean assignment is imminent. Traders often sell puts or calls that drift in the money, especially in high-volatility names. What matters more is how much time value is left.

Take the case shown in the screenshot above: the put is deep in the money, but the trader also holds a long call at the same strike. This is a synthetic long stock position. In this case, even though the short put is deep in the money, there's no real reason to fear assignment. That’s because the trader holds a long call at the same strike price, forming a synthetic long stock position. Whether assignment happens or not, the risk and payoff are effectively the same as owning the stock. The trader is already exposed to the same directional movement. In fact, with both legs in place, the strategy is balanced and self-hedging.

There's no urgent risk, no sudden margin surprise—just a shift in how the position is held. So even if the short put looks scary on its own, the overall structure is stable and intentional.

Most early assignments happen just before expiration—especially on Friday. The closer you get to expiry, the more likely it is that your short in-the-money options will lose all their extrinsic value. For short calls, assignment risk spikes even earlier if there’s an upcoming dividend. That’s because call holders may want to exercise just to claim the payout.

One important point to remember: assignment never happens during market hours. It’s a back-office process that takes place after the close, typically based on end-of-day decisions from option holders. So during the trading day, you won’t suddenly find yourself assigned—there’s time to act. (For more details on how assignment processing works and when it shows up in your account, see Part 1: Assignment explained.)

A simple habit is to check your short options one or two days before expiration. If they're in the money and trading at or near their intrinsic value, you may want to close or roll them. The same goes for any short call that’s in the money heading into an ex-dividend date.

Avoiding assignment is often just a matter of timing. Watch your short options for signs of declining time value. Monitor dividend schedules. And take a proactive approach to managing risk. Whether you want to avoid assignment—or accept it on your own terms—the more you understand the warning signs, the more control you’ll have.

It’s not about avoiding assignment at all costs. It’s about choosing when it works for you.

| More from the author |

|---|