Outrageous Predictions

Executive Summary: Outrageous Predictions 2026

Saxo Group

Christopher Dembik

Head of Macroeconomic Research

Summary: There is an emerging trend: central bank liquidity is slowly turning.

There is only one thing that really matters these days, and it is global USD liquidity. We operate in a dollar-based world, so USD liquidity serves as a key driver of the global economy and financial markets. Since 2014, the world has faced a structural problem of dollar shortage on the back of the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT) and lower oil prices leading to less petrodollars in circulation.

A dollar shortage implies a more volatile environment, a growth slowdown, deteriorated financial conditions, higher USD funding costs — especially for non-US banks — and a sell-off of risk assets. Emerging markets are among the most vulnerable, as noticed in Spring and Summer 2018 when they were hit by high volatility and capital outflow.

In recent weeks, USD funding problems have increased again. Investors must pay higher premiums to swap euros, pounds, Australian dollars and yen into USD for three months. There is a wide range of explanations behind this, but a key factor is the agreement reached on 2 August concerning the US debt ceiling. It is suspended for two full years and, as a result of the compromise, the Treasury plans on borrowing an additional $443bn over a three-month period, versus only $40bn in the previous quarter. This is will have major consequences for USD liquidity.

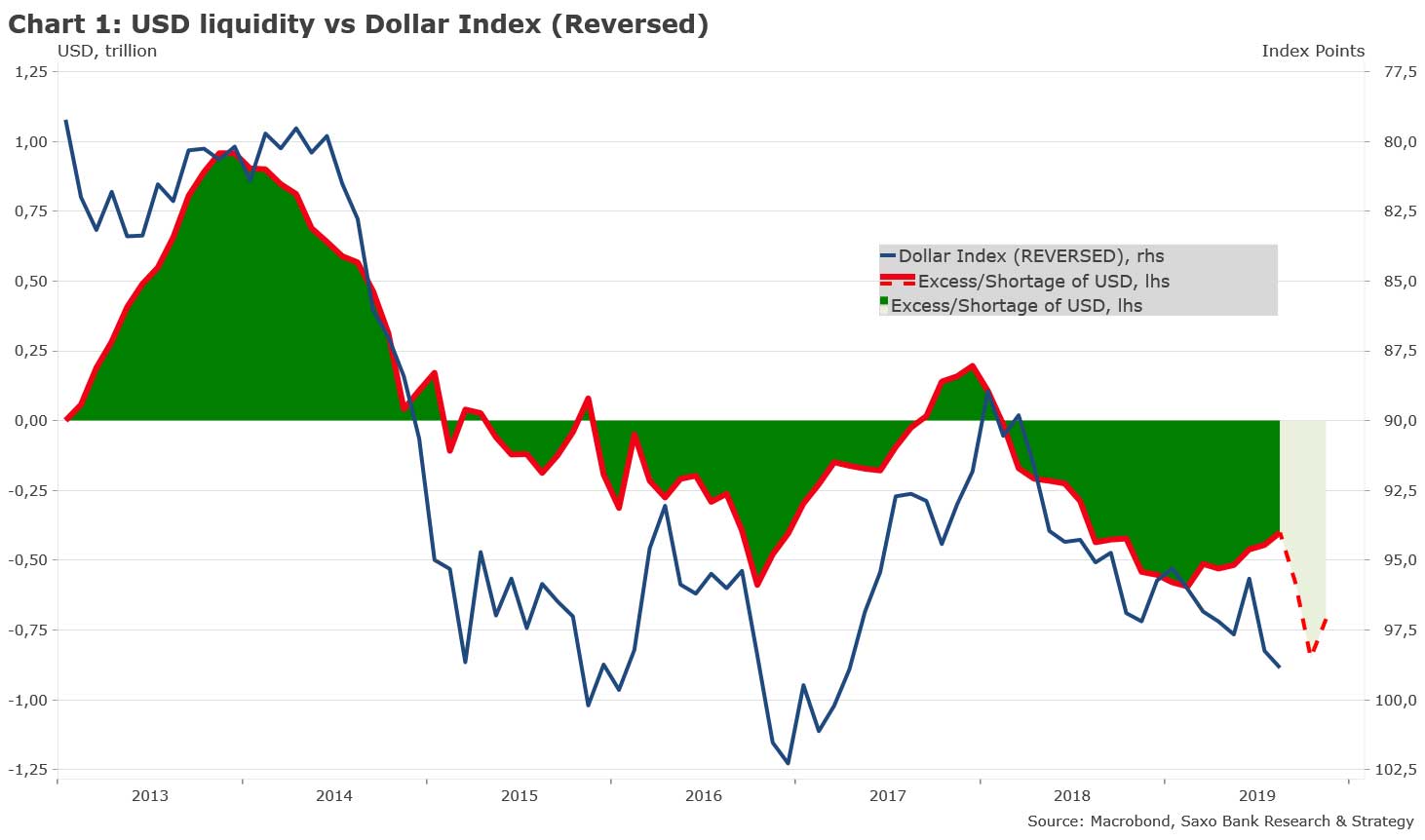

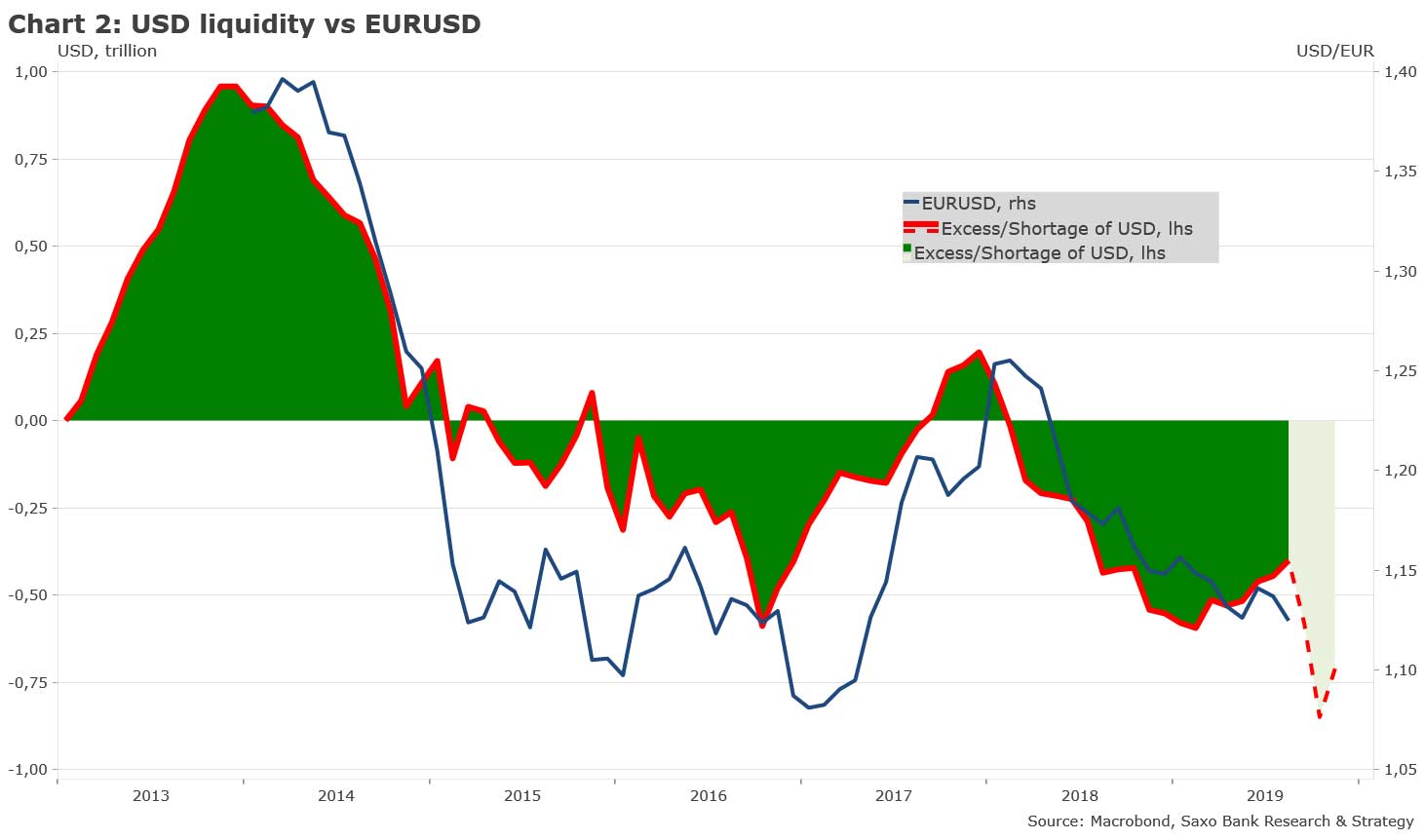

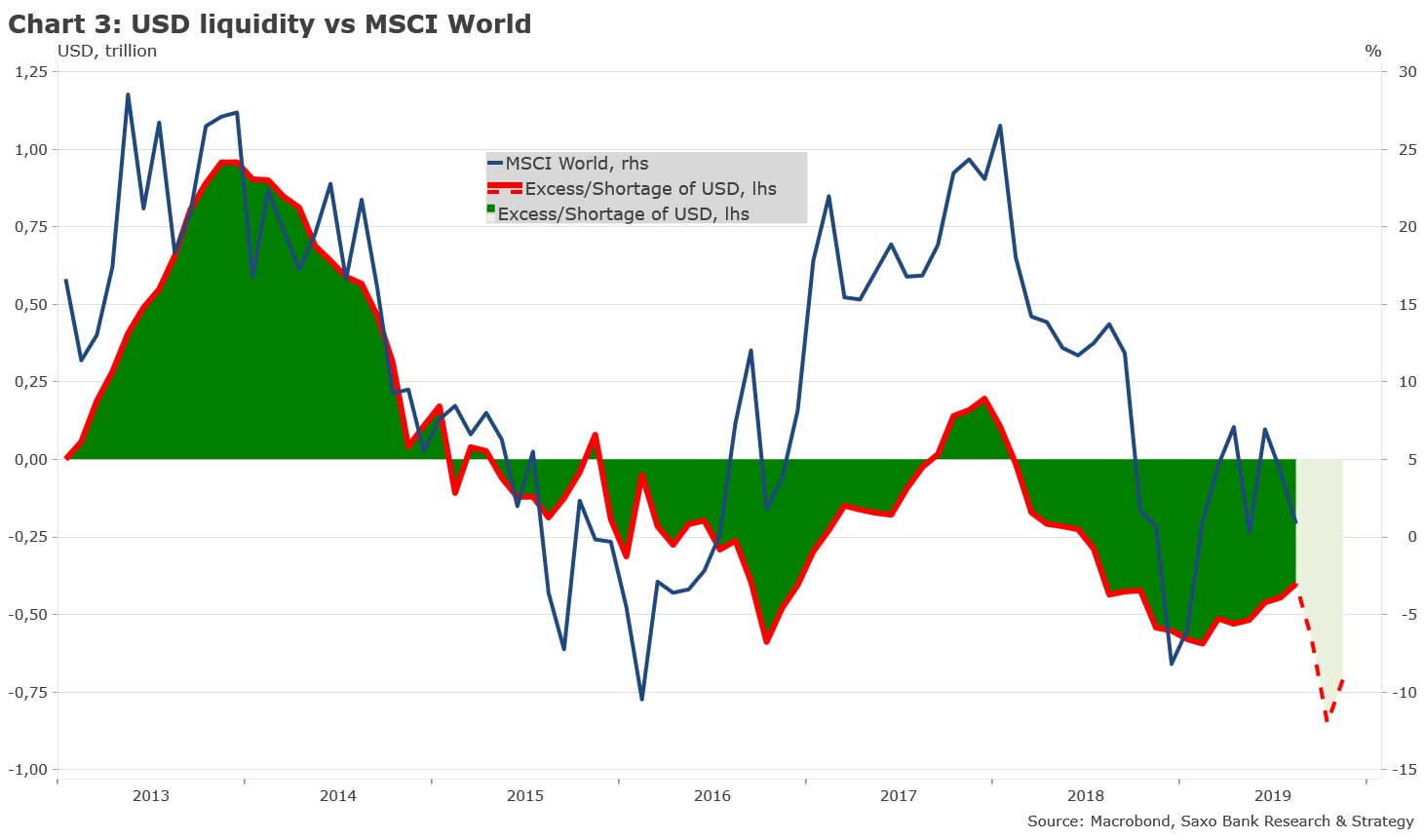

To assess the risk of USD shortage, we use as a proxy the evolution of excess dollars in the US banking system. This is a very good indicator as, in a period of dollar shortage, excess reserves at the Fed stop growing. As of now, the dollar shortage already stands at $445bn, and it may reach an annualised peak of between $800-900bn in the coming months. As you can see in the charts below, there is a strong correlation between excess dollars and a wide range of assets, including EURUSD, DXY and MSCI World.

The massive US Treasury issuance taking place in a period of pre-existing high USD demand will drain liquidity out of the market and further tighten financial conditions in the fall (October/November), ultimately increasing risks to market segments that are already in a fragile position.

Going into 2020, the view is more positive, as financial conditions and USD liquidity will improve. Central banks should go big in the coming months to cope with global trade recession, trade war friction and global slowdown.

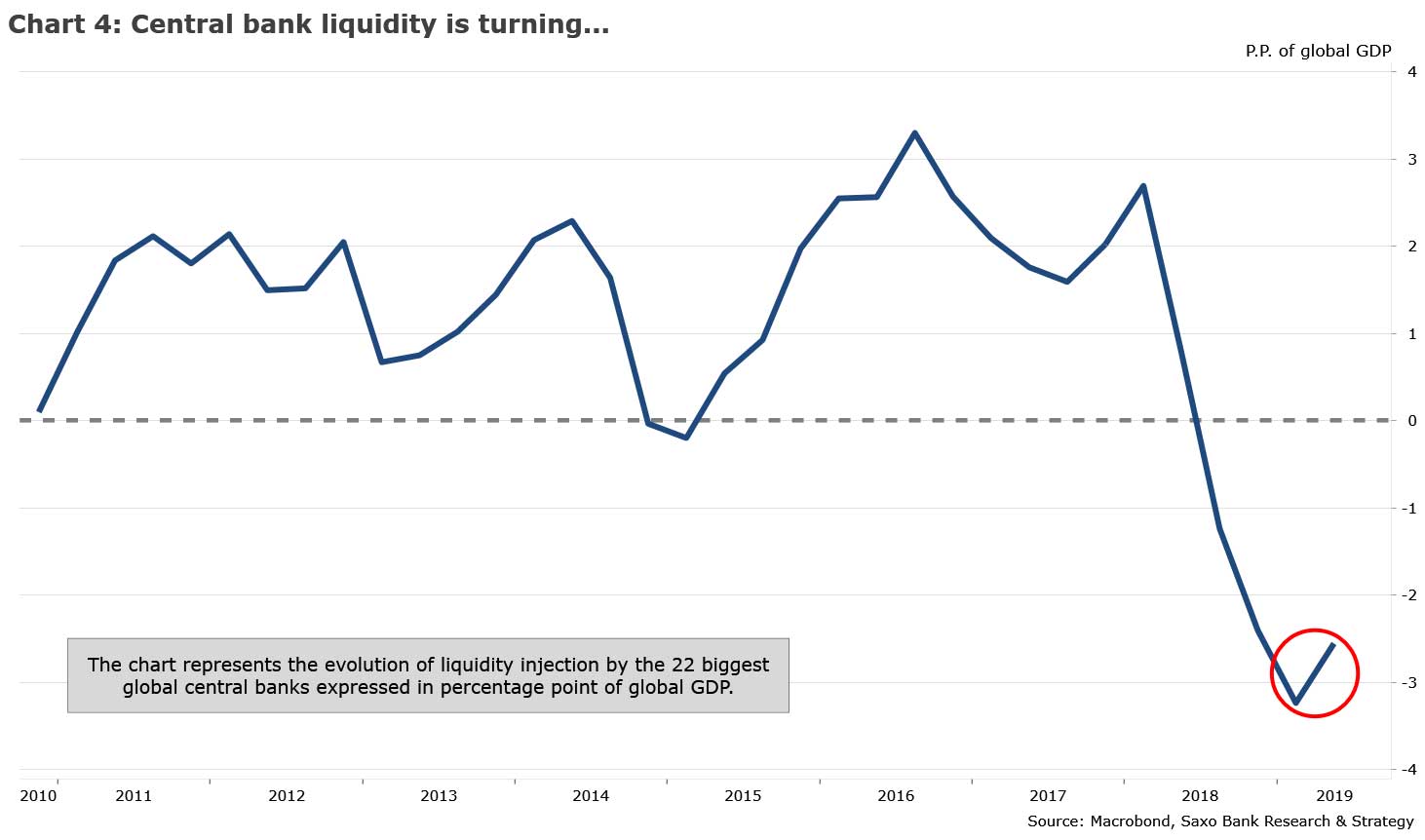

The chart below tracks the evolution of liquidity injection by the 22 biggest global central banks expressed in percentage points of global GDP. After years of massive central bank asset purchases, central bank liquidity has started to contract since early 2018.

Based on the latest data, there is an emerging trend: central bank liquidity is slowly turning. It is still deeply in contraction territory, but it is moving upwards, currently at minus 2.5% of global GDP. For now, the bulk of the improvement is related to positive liquidity injection from the BoJ. Other global central banks will follow as tightened financial conditions push the Fed into a dovish corner and as the ECB will need to support the euro area economy for a prolonged period.

We may also start to see an improvement of our favorite macro gauge, the global credit impulse, that points out to a potential global growth rebound in H1 2020, mostly driven by the US. Based on our latest update, US credit impulse stands at its highest level since early 2018, at 1.2% of GDP. The effect of the credit impulse will be amplified by fiscal push in many countries.