Outrageous Predictions

Executive Summary: Outrageous Predictions 2026

Saxo Group

Head of Macroeconomic Research

At the end of 2017, the consensus embraced the “synchronised global growth/reflation” narrative. Three months later, analysts are struggling to find reasons for higher inflation and are starting to realise that synchronised global growth isn't happening.

The hopes of reflation seen at the start of this year proved to be short-lived despite fears of a trade war. In the G7-countries, average inflation has been stable around 1.7% over the past year and in BRICS+Indonesia, where inflationary pressures are traditionally higher, we observe a clear convergence of inflation rates with developed countries. Inflation in emerging countries is running at its lowest level since the Great Financial Crisis at only 3.2% YoY.

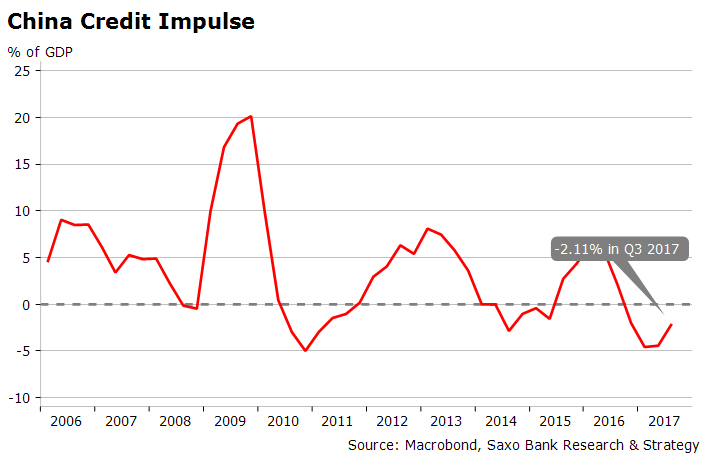

On the other hand, there are more and more signs that global growth might have reached a peak. Slowdown has already started in China as credit impulse have turned south since the beginning of 2017. It is currently running at minus 2.11% of GDP, after reaching a lowest point since 2010 in Q1 last year.

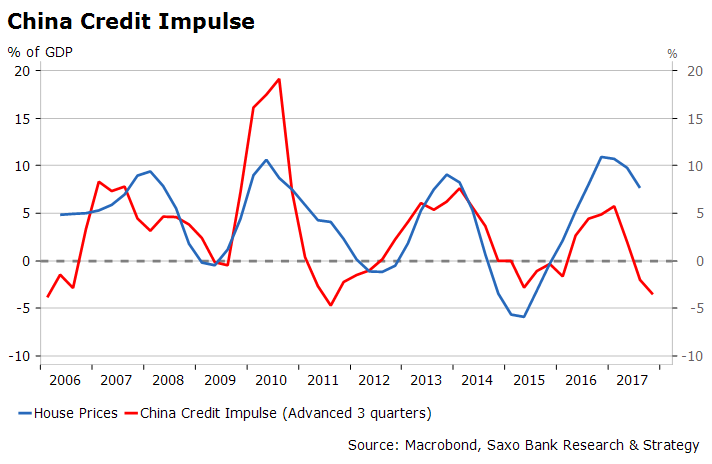

We believe that China’s deleveraging is premeditated and it will be monitored in the future by Wang Qishan. This close ally of President Xi was appointed vice president at the beginning of March after a successful fight against corruption. Although his competence is not in question, the deleveraging process can derail at any time due to China’s wall of debt. One of the key weakness points is the real estate sector, which has been disproportionately fuelled by inflow of loans over the past few years. Since China’s credit impulse leads house prices by three quarters, as we see below we can expect further downward pressure on prices in the course of the year. The tricky task for China is to lower prices without triggering a collapse of the market that would weaken the entire banking and financial system. Banks’ dependence on real estate loans is dangerously high: over the past twenty years, real estate and banks have a stunning correlation of near 0.90.

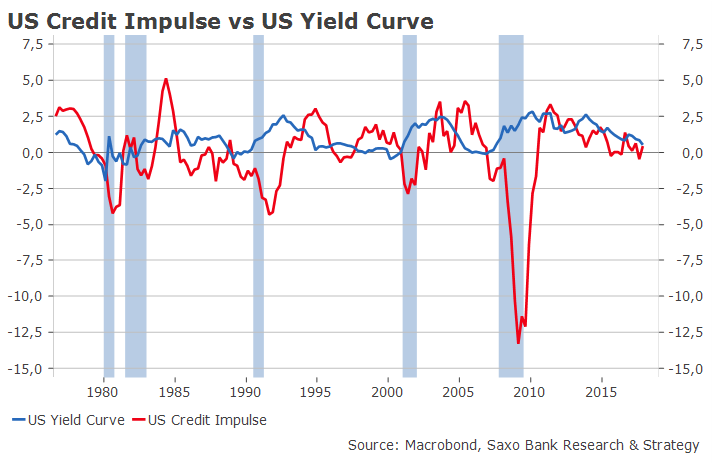

In other parts of the world, the economic outlook is not brighter. There are little signs that President Trump’s tax reform will much extend the business cycle. In addition, Q1 GDP is unlikely to come out rosy: durable goods and retail sales have started the year down and there has been no clue of tax bill-inspired capex boom yet. The only hope is to have a productivity miracle which is, objectively, quite unlikely. All of our leading indicators – contraction in US credit impulse, lower but not yet negative C&I loans growth and a flattening yield curve (US 10v30 swap spread almost inverted!) – are indicating that the United States is close to the end of the cycle.

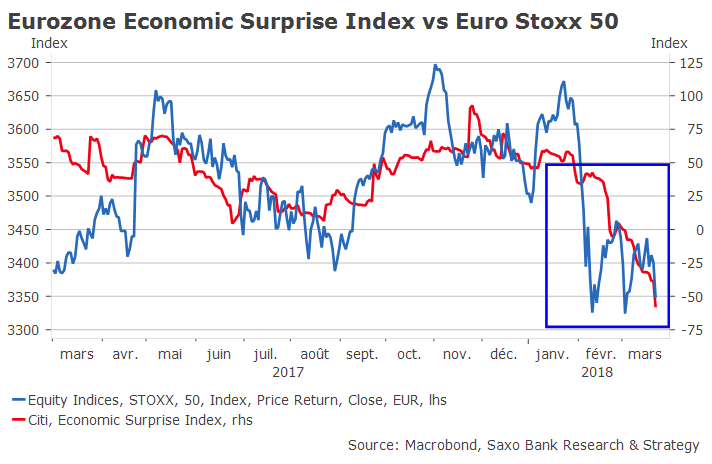

But certainly the most unpleasant surprise comes from the euro area. Growth momentum here is much stronger than in most other regions but recent data from Markit and the European Commission seem to indicate that growth has certainly reached a plateau. Citi Eurozone Economic Surprise Index has collapsed in Q1, adding downward pressure on European stocks. The index is currently the lowest among G10, at -57.9.

The euro area remains too export-dependent and demand is still too weak. In addition, the euro area crisis is far from being over: looking at Spain and Italy’s trade balances, we notice that most of the improvement is due to higher extra-euro area demand and a weak currency. The restoration of competitiveness is still a work in progress in many European countries.

Weaker growth is happening at the worst time because risks are popping up everything. We are facing a unique combination of rising geopolitical risk, higher global protectionism coupled with monetary policy tightening.

Protectionism is a much more complex issue than it seems

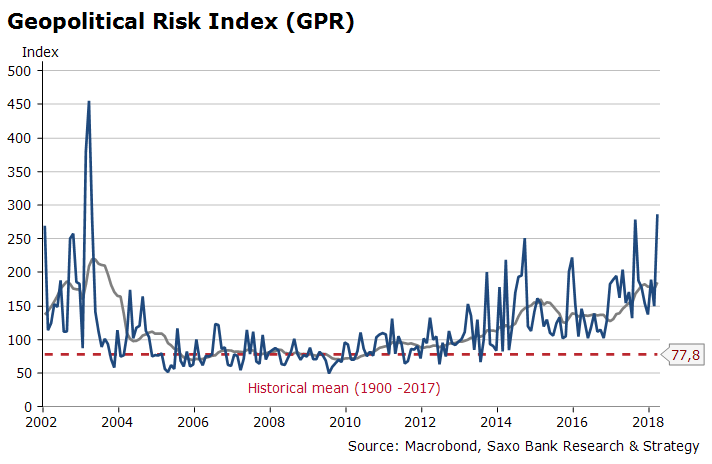

Since Trump has first announced the steel and aluminum tariffs on March 1 the market has been in risk aversion mode. The Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) is at its highest monthly level in March since the Iraq war in 2003, currently at 286. Investors have favoured safe havens, such as gold, at the expense of equity markets. Stock markets which are the most exposed to international trade, such as the Japanese Nikkei, have fallen sharply.

Explanation: The Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) was developed by Caldara and Iacoviello. It counts the number of articles related to geopolitical risk in 11 national and international newspapers for each month as a share of the total number of news articles. More information about the methodology can be found here.

However, in the longer run, the risk of a real trade war between the USA and China (this is the real issue, not the noise about US-Europe trade war!) is difficult to predict and to price. With all the necessary caution due to the fact that Trump is totally unpredictable, we believe that this scenario is very unlikely right now. There is little doubt that Trump seems to believe that states with a surplus have the most to lose in a trade war but we can assume he is pragmatic enough to avoid a frontal confrontation with Beijing. Whether he likes it or not, he needs China to finance US debt and support the dialogue process with North Korea. So far, protectionist measures have been largely smoke and mirrors. They mostly aim to please US business by adopting an aggressive tone against China’s IPR infringement without taking any measures likely to provoke the wrath of Beijing.

For its part, China has no interest in a trade war. President Xi has just consolidated power and has to cope with a domestic economic reset. It is highly unlikely that he would seek to blow up financial markets with war on US dollar or T-bonds right now. Actually, the smartest retaliation for China would be to decide asymmetric strikes at core US business such as GM or Boeing. For example, it would be much easier and as effective for China to send hygiene inspectors to factories essential for the US production chain and, for whatever reason, to shut down the plants for a couple of weeks or longer.

To sum up, China and the United States have no other choice than to reach an agreement about trade/IPRs issues.

The risk of policy error should be the real burning issue

What really worries us in the long term is the risk of policy error resulting from monetary policy normalisation. Since 2008, markets have regularly swung between period of calm and shock. In roughly two out of three cases, the periods of shock has occurred due to central banks (adjustment in forward guidance, misinterpretation of central communication, uncertainty about inflation…). So far, global financial conditions remain quite accommodative and the Fed’s normalisation process has been rather successful.

However, the ability of central banks to raise rates further is increasingly being constrained due to the impact of liquidity withdrawal on volatility, credit and ultimately on zombie companies while growth is losing momentum in core countries. A market shock that may seem trivial at first can become the trigger for a bear market. What is even more striking is that more and more investors are expecting this scenario to happen any time soon. The question is to know what the trigger will be: will it be when the federal funds rate will cross the threshold of 2% or 2.5%? When the US 10-year government benchmark bond yield will be over 3.5%? No one knows…Therefore, in these circumstances, we need to be vigilant.